A Guide for Organizing, Cataloging, and Preserving

Collections of Papers, Photographs, and Other Records

advice on archival management to help you set up, maintain, and provide access

to small collections of personal papers, family records, and other holdings

This informal guide is a compilation of information from readily-available sources in online and printed formats. It is an introduction to a complex and difficult subject that is intended to help you organize and preserve collections of papers and other possessions and to make them available for use. As a short introduction by an interested amateur, it does not pretend to be an authoritative reference tool and should not be taken as one.

Brief Overview

You can use this brief introduction to archival management as a reference guide, an informal tutorial on setting up a small repository, or as an introduction to a phased approach to organizing and conserving a small family or personal collection. Take a moment to scan the topics that are treated in the list of tasks shown directly above.

You can use this brief introduction to archival management as a reference guide, an informal tutorial on setting up a small repository, or as an introduction to a phased approach to organizing and conserving a small family or personal collection. Take a moment to scan the topics that are treated in the list of tasks shown directly above.

If your holdings are not extensive, your time limited, and your budget tight, you should probably make a relatively modest first set of steps (as described in the Start Small section) and then decide whether to go further. If you have a relatively large collection on which you have already been working for some time, you might wish to begin somewhere within the tasks that follow the Start Small section.

If you do not decide to start small, and if you have not already done so, you should begin by doing a first draft of an archives policy statement. Next you should gather and analyze information about the collections you hold and then physically organize and arrange the contents of each of them into a useful order. While doing these things you should make sure you have the data you need to create catalog records and other appropriate finding aids for your own administrative control and so that your users can identify and locate relevant materials. You should put items into folders, boxes, and other types of archival housing. You should make use copies, as appropriate, either in hard copy or online, or both, being careful not to violate copyright or the privacy rights of people who have a direct interest in the contents of the collection (as, for example subjects of reports or authors of papers). You should make sure the environment in which the collections are to be stored is as close to ideal as you can manage. And you should take care to document the procedures you have used throughout in a log book or similar record.

Some of these steps must be done before others, but some can be done as it suits you. You will probably find it convenient to begin a step, such as gathering information about the collection, then leave it to do other steps, such as organizing and housing items, and then return again to information gathering as you get ready to create your catalog records and finding aids.

Start Small

Essential Elements of a Phased ProgramThere is no need to embark on a major effort to manage your collection. You can limit yourself to these first steps or use them as the starting point for a phased program. It is obvious that some of these first steps must be taken before others but many can be done in whatever order you please.

Record keeping is important. You should draft a brief checklist of what you plan to do; prepare records, however informal, about the collection and its contents; and jot down notes -- a journal of some kind -- indicating what you have done and when you did it.

You should examine each item in the collection, making notes about problems you see and actions you plan to take. In handling the items, keep in mind these simple rules:

1. Examine

- Before handling any items wash your hands or wear thin cotton gloves.

- Put a clean blotter or large sheet of paper on the table or other work surface you will use.

- Place the items at least three inches from the edge of the work surface.

- Do not be tempted to make repairs unless you are certain you know what you are doing.

- Do nothing to any item that cannot be undone, no procedure that cannot be reversed.

- Never put anything sticky on an item -- no adhesive tape, no glue, not even a sticky note.

- Do not staple items or use metal clips on them.

- Remove existing staples and clips if you can do so without causing damage.

- Pry off staples by lifting the tips with a knife blade; do not use a staple remover.

- Slide stiff plastic under both sides of a paper clip then slide it off.

- To remove dust, brush lightly with a soft brush.

- Brush away from yourself and clean up the dust frequently.

- If there is evidence of mildew or mold, bush off and use a dust mask to avoid inhaling the stuff.

- It is best to flatten folded items if this can be done without damaging them.

- Remove any deteriorated wrappings that are not part of the item.

- Do not write on any item.

- Decide how to arrange the items.

- Keep them in original order if possible.

- Otherwise use your common sense to arrange in a natural order.

- During examination, consider what storage supplies you will need to purchase.

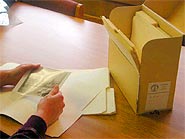

2. Place in archival containers

- Obtain whatever boxes, folders, sleeves, and other supplies you think you will need.

- Remember than these storage supplies must meet archival standards.

- In general, they should be alkaline or buffered rather than simply acid-free.

- Remember that plastic is not suitable for long term storage.

- Instead of ordinary plastic, obtain archival quality clear polyester sheets and sleeves.

- Uncoated polypropylene or polyethylene is also acceptable.

- Never use PVC plastics (polyvinylchloride).

- Group items in sleeves, folders, and boxes in accordance with your decisions on arrangement.

- Tie up loose book boards and spine pieces with soft cotton tape.

- Or put the book in an envelope or box.

- Lie large, damaged books flat on a surface; do not stand them on their spines.

- Maps and other large documents should be stored flat if possible; do not fold.

- If it is impractical to store them flat, maps may be lightly rolled up and put in a box or wrapper.

- Photographs should be placed in archival polyester sleeves and stored separately.

- Sheets of highly acidic paper (such as newsprint) should either be put in polyester sleeves or they should be interleaved with sheets of buffered paper.

3. Make backup copies of copyable media

Make multiple backups of all digital photographs and other valuable media. Audio cassettes, videotapes, floppy disks, hard drives, CDs, DVDs and other copyable media all have a limited life expectancy and are subject to both gradual deterioration and catastrophic failure.

4. Make photocopies of newsprint and other highly acidic paper

Make photocopies of newspaper clippings and other items on highly acidic, short-life paper. Electrostatic (xerographic) copying is best (copiers that use heat fusing rather than ink jet printing). It is best to copy onto paper that meets permanent and durable paper standards, or, at the least, paper that is acid-free. If you can, you should digitally scan high-acid items as well as photocopying them.

5. Store the archival containers

- Light: It is best if your storage area is dark most of the time. If at all possible, the items in your collection should never be exposed to sunlight.

- Temperature and humidity: Ideally, the temperature and humidity should be at the low end of the comfort zone: a bit cool, a bit dry. It is most important that they fluctuate up and down as little as possible.

- Dust, pollution, and other airborne contaminants: The storage area should be as free from airborne contaminants as you can manage.

- An interior closet is a good choice: Your best choice might be an upper shelf or set of shelves in one or more closets within a living area (not in an unheated basement or uncooled attic).

6. Plan for future tasks

- Review the other sections of this guide and jot down a plan for future action.

- List items that you think might need professional conservation treatment. These will probably be items that are especially old or otherwise precious and that are unusually fragile and deteriorated.

- Consider drafting a reformatting policy, that is a plan for making copies that can be frequently-handled and displayed.

- If they can be digitally scanned, consider scanning as well as (or even instead of) photocopying. Digital images can be printed for use, saved as backup copies, and made accessible both on site and via the internet. They are not inherently long-lived but can be infinitely replicated and, if replicated before deterioration sets in, will be available for use as long as devices for decoding them remain available.

Here are some links to further information on first actions to manage a small collection:

- A Manual for Small Archives (pdf), Archives Association of British Columbia

- Caring for Private and Family Collections, Northeast Document Conservation Center

- Care for your family records, Archives Department, University System of Georgia

- Preserving Personal Papers and Photographs: General Guidelines, Arizona State Archives

- Care of Family Papers and the Home Library (pdf), Preservation Department, Cornell University

- Preserving Your Family Treasures, Preservation Department, Library of Congress

- Preserving my Heritage, Canadian Conservation Institute

- Caring for your books and documents at home (pdf), Norfolk Record Office (UK) Information Leaflet

- Preserving Family Collections, National Library of New Zealand

- AIC Caring For Your Treasures, American Institute for Conservation of Historic and Artistic Works

- Conservation/Preservation Information for the General Public, Conservation Online, American Institute for Conservation

- Caring for Personal Collections: Selected Online Resources, Preservation Services Department, Harvard University

- Engaging online education: Mastering digital archives, in Archives in the Digital Era by Richard Pearce-Moses

- The Care and Preservation of Archival Materials, Benson Ford Research Center

Here are some lists of sources of boxes, folders, and other archival supplies:

- Conservation and Preservation Supplies, a DMOZ open directory listing

- Publications, Software & Supplies, from Cyndi's List of genealogy sites on the internet

- Preservation & Conservation Vendors, from Cyndi's List of genealogy sites on the internet

- Sources For Archival Supplies, Missouri State Department of Records and Archives

- Archival Supplies Resources, Kansas Historical Foundation

- Sources of Archival Supplies, Concordia Historical Institute

- Conservation Online (CoOL) List of Suppliers, lists sources of conservation supplies and services ("This page contains lists of preservation-related suppliers/service providers, both for-profit and not-for-profit. They include both web resources and info about entities not accessible via the web.")

- suppliers list from the Northeast Document Conservation Center. ("An up-to-date database of vendors that provide preservation or conservation supplies, services, and equipment.")

- DOCUMENT CONSERVATION, list of suppliers, sources for conservation supplies from the Indiana Historical Society

- Vendors contractors and suppliers, a state-by-state listing of preservation services and suppliers from the Council of State Archivists

- Conservation and Library Resources, on PearlTrees.com

Online Courses and a Software Program

Take a look at these two online courses. Both are self-instructional and intended to provide basic training in archival practices.

- Preservation 101 from the Northeast Document Conservation Center (scroll down for link to the free self-guided version)

- The Basics of Archives from the American Association for State and Local History

Also review The Archivist's Toolkit of the Archives Association of British Columbia. While not an online course, it is structured so that it can be used as one.

The Archivists' Toolkit is an award-winning computer program that automates most archival processes. It intended for use in small as well as larger archives, by people who are untrained as well as those who have professional training. It can be used on a single personal computer (Windows or MAC) or in a network environment. It is an open-source system and there are no charges for downloading or using it. Developed in 2004 by a group of academic archivists with foundation support, it is continually upgraded and improved.

In addition to automating the core processes of archival work (accessioning, cataloging, preparation of finding aids, record keeping, and the like), the system is fully searchable and can prepare administrative reports. It also has tools by which a collection can be made accessible on the Internet.

Here are links to further information about the system:

- Introduction to the Archivists' Toolkit from the organization that produced it

- Archivists' Toolkit: User Manual, contents page in html

- Archivists’ Feedback on Archivists’ Toolkit from a survey of Toolkit users

- Archivists’ Toolkit Receives Society of American Archivists’ Award

Managing Small Archives — The Main Elements

Draft an archives policy statement

For further information on this topic see the Getting Started section of the Manual for Small Archives, prepared by the Archives Association of British Columbia and Policy Development (both pdf), which is Chapter 2 of the Canadian Council on Archives handbook, Basic Conservation of Archival Materials (also known as the Red Book).

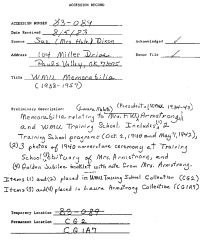

Acquire and accession the contents of the collection

Once you have a first draft of an archives policy, consider how you will bring items into the collection. You probably already have lots of material waiting for your attention, but, even so, you should now ask yourself whether how you will add more of them and, if so, how. Will you buy, borrow, request donation, receive from an organization by mutual agreement? Regardless of where new contents come from, be sure to document each new acquisition. Make accession records that describe the items, give the source, state your legal right to them. You may wish to make the records in the form of receipts, one copy of which you retain and the other going to the source of the items.

Once you have a first draft of an archives policy, consider how you will bring items into the collection. You probably already have lots of material waiting for your attention, but, even so, you should now ask yourself whether how you will add more of them and, if so, how. Will you buy, borrow, request donation, receive from an organization by mutual agreement? Regardless of where new contents come from, be sure to document each new acquisition. Make accession records that describe the items, give the source, state your legal right to them. You may wish to make the records in the form of receipts, one copy of which you retain and the other going to the source of the items.

Your acquisition record contains the basic information needed for accessioning each new item or group of items that you bring into the collection. Each item or container of items needs to have an accession record and an accession number. You can put a preliminary number on containers now and a final one later, after you have made final decisions on arrangement and have put items in archival storage containers. A preliminary numbering scheme could be a simple serial number or a composite number including a date code and serial number. See the section on organizing the collection for information on the accession numbering.

As you would expect, accession records are your means of keeping administrative control over the collection. They show your legal right of possession and they give basic information that you will need as processing proceeds.

The Archivists' Toolkit User Manual of the Archives Association of British Columbia has links to some sample forms including accession records and a deed of gift. There are also sample forms in Appendix A of the Manual for Developing a Baptist Archives.

For further information on this topic see the Acquiring, Appraising, and Accessioning section of the Manual for Small Archives, prepared by the Archives Association of British Columbia, and also see the Resources section of this web page.

Gather information about the collection

Assemble your accession records and all the other records you can find about each collection and its contents. These might include documents prepared by others who possessed the materials at one time or another, forms that describe them, legal documents or agreements concerning them, records retention schedules, or administrative papers of one kind or another. To pull this information together you may find it useful to do some research on the internet, by telephone, in written inquiry, and in library searches. You may find yourself adding to this information as your proceed with other processing tasks. It's not something you have to do exhaustively before you do anything else.

Assemble your accession records and all the other records you can find about each collection and its contents. These might include documents prepared by others who possessed the materials at one time or another, forms that describe them, legal documents or agreements concerning them, records retention schedules, or administrative papers of one kind or another. To pull this information together you may find it useful to do some research on the internet, by telephone, in written inquiry, and in library searches. You may find yourself adding to this information as your proceed with other processing tasks. It's not something you have to do exhaustively before you do anything else.

Do a preliminary review of everything in the collection. Learn what you can from a quick first once-over. Take quick notes of what you find.

Ask yourself some questions about arrangement. Is there a natural order in which the contents have been or should be kept -- by date, for example, or in a numerical record-number sequence? What was the order in which they were originally kept?

Are there restrictions on access to the contents for reasons of privacy, by law or regulation, or by a contractual agreement?

What is the historical context of the collection; what relevant events took place at the time or since that a person using the collection should be aware of?

Look for information that you will need in creating the catalog record and the register or finding aid for the collection. See the section on cataloging, below.

The Manual for Developing a Baptist Archives has some example forms for acquiring information about organizational records in the Records Survey section of its appendix. For further information on this topic see Links to sources on cataloging in the Resources section of this web page, and in particular see Introduction to Metadata from the Getty Research Institute.

Analyze the contents of the collection

Before you analyze the collection take a look at your archives policy. Ask yourself some basic questions. Why does this collection exist? Why should I put time -- my work hours -- into organizing and describing it, insuring its preservation, and making it accessible for others to use? What is its main focus? What are its strengths and weaknesses in conveying the importance of this main focus to the world? Am I the right person to be performing this work, or is this so extensive, important, complex, and fragile that professional experience is needed? Do I have the time, resources, and skill that will be needed to carry out this work from beginning to end? Or, maybe, is this work likely to have little enduring value outside my own interest? And finally, do I have full legal right to process the collection or do the rights of others impinge upon mine and restrict what I can do with it?

Before you analyze the collection take a look at your archives policy. Ask yourself some basic questions. Why does this collection exist? Why should I put time -- my work hours -- into organizing and describing it, insuring its preservation, and making it accessible for others to use? What is its main focus? What are its strengths and weaknesses in conveying the importance of this main focus to the world? Am I the right person to be performing this work, or is this so extensive, important, complex, and fragile that professional experience is needed? Do I have the time, resources, and skill that will be needed to carry out this work from beginning to end? Or, maybe, is this work likely to have little enduring value outside my own interest? And finally, do I have full legal right to process the collection or do the rights of others impinge upon mine and restrict what I can do with it?

In order to create the catalog record and finding aid, you must distill the information you gather so that it can be presented concisely without sacrificing accuracy. You need to decide what of it is most significant and what is secondary. You will probably find yourself going back over this process repeatedly as you learn more about the collection and gain confidence in your ability to judge what is important and what is not.

As you examine the items in the collection you should also keep in mind the need to make decisions on organization and arrangement. Review the section on organization and arrangement, below. Make notes on your decisions about this subject.

Similarly, you should make notes on the physical condition of items and the need to provide appropriate housing for them. Record treatment that will be needed and list the housing supplies, such as acid-free (or, preferably, buffered) folders and boxes, that you must obtain. Review the section below on conserving contents so you know whether to remove paper clips, staples, old tape, and the like.

As you did while gathering information, you must keep in mind the categories of data that you will later put in the catalog record and finding aid. See the Catalog section, below.

As above, for further information on this topic see the Resources section of this web page, and in particular see Introduction to Metadata from the Getty Research Institute.

Organize the contents of the collection

Decide first whether the existing organization of the collection is appropriate. As a primary rule, you should keep items in the order in which they were originally created, maintained, and used. If there is no order or if the original order has been disturbed, try to determine what the natural order of the items should be. For example sets of official documents having record numbers should probably be kept in order by those numbers. Collections of correspondence should probably be arranged by correspondent and sub-arranged by the date of individual letters. For preservation reasons, you may have to subdivide your arrangement by format, keeping photos separate from cassette tapes, for example.

Decide first whether the existing organization of the collection is appropriate. As a primary rule, you should keep items in the order in which they were originally created, maintained, and used. If there is no order or if the original order has been disturbed, try to determine what the natural order of the items should be. For example sets of official documents having record numbers should probably be kept in order by those numbers. Collections of correspondence should probably be arranged by correspondent and sub-arranged by the date of individual letters. For preservation reasons, you may have to subdivide your arrangement by format, keeping photos separate from cassette tapes, for example.

Most collections need to be arranged in groups. They are grouped by format — whether manuscript, book, photograph, or one of the recorded media. They can also be grouped, or sub-grouped, by the creator: the person or organization that created them. They can also be grouped under organizations that were responsible for their creation even when there were individual personal authors.

As you make decisions on arranging the collection, you may wish to make an organizational chart to help you record your decisions. The Manual for Small Archives gives an example of one.

Use unambiguous terms to label the groups and subgroups, terms that are distinctive and not likely to cause confusion. Once you have established your record groups, keep them. Do not be tempted to rename them after you have created your catalog record and finding aid unless you can't avoid it.

Within groups and subgroups you may find it useful to assign record series. They can be numerical, chronological, or alphabetical.

You must provide a location code, shelfmark, or other identifying designation for each container into which items are placed. As you arrange the collection, make decisions on what scheme you will use for this set of codes. No folder, box, or other container may be without an identifier for filing and retrieval. For obvious reasons, your codes should be sequential and simple enough so that they can easily be kept in proper order. Here is one scheme:

A common system is to use the last two or three digits of the current year and a sequential number for each accession received that year. Thus the third acquisition in 1987 would be accession number 987.3; the fourteenth in 1988 would be 988.14. Each accessioned unit will receive its own number, regardless of whether it consists of two letters, six boxes, three photographs, or a mixture of all media types. Thus, an accession including four letters, six photographs, and eight maps will be number 987.5; the different items might have item numbers within the accession, such as 987.5.1 or 987.5.16.

{Source: Manual for Small Archives of the Archives Association of British Columbia}

For more information on this subject see Links to Sources on Organizing Collections in the Resources section of this web page and in particular the Society of American Archivists' page on Labeling and Filing and the Organizing Archival Material section of the Manual for Small Archives.

Put materials in archival containers and give them a good storage environment

For basic steps on this topic review the Start Small section, above.

The contents of your collection should be stored in containers that are sturdy and free of contaminants that might damage their contents. Most cardboard boxes and file folders contain acids that contaminate paper and other items and must not be used. There are quite a few suppliers of acid-free or buffered storage containers. The Links to sources of supplies in the Resources section gives a few of them.

The contents of your collection should be stored in containers that are sturdy and free of contaminants that might damage their contents. Most cardboard boxes and file folders contain acids that contaminate paper and other items and must not be used. There are quite a few suppliers of acid-free or buffered storage containers. The Links to sources of supplies in the Resources section gives a few of them.

Whatever storage container you choose make sure you observe the fundamental rule of conservation: do nothing that cannot be undone if necessary.

In addition to providing proper housing, it's important that you provide your collections with a non-harmful environment. Very few storage areas are able to meet full archival environmental standards, but do the best you can. Ideal environments have low-to-moderate temperature and humidity which remains constant. Locations with substantial temperature and humidity fluctuations are more harmful than locations in which fluctuations are small but conditions are warmer and more humid than the ideal. Light, particularly ultraviolet light from the sun or from most fluorescent lamps, is damaging and should be avoided. Window shades and flourescent bulb filters that absorb UV light are readily available. Air quality should be as good as can be managed. Make sure that heating, air conditioning, and ventilating equipment is properly maintained (including regular changing of filters). Avoid areas that are infested by damaging agents such as insects, rodents, mold, or fungus.

An environment that is kept comfortable for human habitation is much better than one that has no environmental controls. Choose a room in the living areas of a house, preferably an interior one. Rooms that are infrequently used are appropriate, for example a storage closet.

Handle archival materials as little as possible. It is a good idea to wash your hands before handling material or, better, use cotton gloves. Prepare a work surface as described in the Start Small section. Keep food and beverages away from materials. Do not use metal paper clips or rubber bands to secure objects together. Remove ones that you find if you can do so without causing damage.

Isolate highly-acidic items, such as newsprint, and, if you can, make archival copies of them. These are usually easy to identify because of their discoloration and brittleness. If uncertain, you can use a pH testing pen to indicate the amount of acidity. To prevent acid migration from one document to another, you should separate acidic items from one another by putting them in clear polyester sleeves or interleave them using acid-free (preferably buffered) paper or glassine sheets. You should also put them in their own buffered folders if possible, rather than interfiling with non-acidic items. When making copies it is better to use an electrostatic (xerographic) copier rather than one that uses inkjet technology and you should copy onto paper that meets permanent and durable paper standards, or, at the least, paper that is acid-free. If you can, you should make digital scans of high-acid items as well as photocopying them.

Isolate highly-acidic items, such as newsprint, and, if you can, make archival copies of them. These are usually easy to identify because of their discoloration and brittleness. If uncertain, you can use a pH testing pen to indicate the amount of acidity. To prevent acid migration from one document to another, you should separate acidic items from one another by putting them in clear polyester sleeves or interleave them using acid-free (preferably buffered) paper or glassine sheets. You should also put them in their own buffered folders if possible, rather than interfiling with non-acidic items. When making copies it is better to use an electrostatic (xerographic) copier rather than one that uses inkjet technology and you should copy onto paper that meets permanent and durable paper standards, or, at the least, paper that is acid-free. If you can, you should make digital scans of high-acid items as well as photocopying them.

Here are some other useful sources of information on housing materials and giving them an appropriate environment.

- Resources For Private And Family Collections from the Northeast Document Conservation Center

- Caring For Your Books And Pamphlets At Home (pdf) from the Norfolk (UK) Record Office

- Environment, Care, Collections (all pdf) which are Chapters 3, 4, and 6 of the Canadian Council on Archives handbook, Basic Conservation of Archival Materials (also known as the Red Book)

- Preservation Leaflets from the Northeast Document Conservation Center, including

- Removal of Damaging Fasteners from Historic Documents

- Storage Methods and Handling Practices

- Cleaning Books and Shelves

- Storage Enclosures for Books and Artifacts on Paper

- Storage Enclosures for Photographic Materials

- Temperature, Relative Humidity, Light, and Air Quality: Basic Guidelines for Preservation

- Monitoring Temperature and Relative Humidity

- Getting Function from Design: Making Systems Work

- Protection from Light Damage

- Low Cost/No Cost Improvements in Climate Control

Conserve materials and protect them against deterioration

Do not attempt any restoration or preservation treatment of an item until you are certain you know what you are doing. If you can afford the cost, it is best to entrust treatment to a qualified professional.

Do not attempt any restoration or preservation treatment of an item until you are certain you know what you are doing. If you can afford the cost, it is best to entrust treatment to a qualified professional.

There are many other resources on preservation. Some of them are listed in the Links to Sources on Conservation of the Resources section on this web page. Take some time to review at least these primary ones.

- Free Conservator Referral Service of the American Institute for Conservation of Historic & Artistic Works

- Preserving my Heritage from the Canadian Conservation Institute

- Care of Family Papers and the Home Library (pdf), an illustrated pamphlet from the Cornell University Library Department of Preservation and Conservation

- Preserving Your Family Treasures from the Library of Congress

- Preserving Personal Papers and Photographs: General Guidelines from the Archives division of Arizona State Library.

- Caring for Cultural Material, from the Australian Heritage Collections Council

- Preservation Leaflets from the Northeast Document Conservation Center, including

- Surface Cleaning of Paper

- Repairing Paper Artifacts

- Conservation Treatment for Works of Art and Unbound Artifacts on Paper

- Conservation Treatment for Bound Materials of Value

- Choosing and Working with a Conservator

-

Create a catalog record and finding aid for each collection

You should create catalog records and finding aids for administrative control and user access.

You should create catalog records and finding aids for administrative control and user access. A catalog record gives basic information about the collection and its contents in a structured format. It gives the collection's title, topics, and the principal names of individuals and organizations that are associated with it. It also contains a brief summary of contents and administrative notes. The finding aid is used to list individual items within a collection and show their location. Catalog records for manuscript collections are formatted like the ones that are used for books. They can be created useing the same bibliographic control software used by libraries, but they can also be made using word processing software or using database programs such as Microsoft Access. They can be printed sheets of paper, one per sheet, and kept in a loose leaf binder, or they can be kept online. They can be retained locally or disseminated online for use in-house and across the Internet. Some small archives are eligible to participate in the National Union Catalog of Manuscript Collections, a program operated by the Library of Congress. Here are links for information about the program and participation in it:

Each catalog record should include (where applicable):

- A location code, shelfmark, or location number for the collection

- The location(s) where it is housed and made available for use

- Its creator(s) and authors, institutional or personal

- Its title or descriptive name

- A statement of extent, how much of it there is, e.g., number of boxes and shelf space required to store it

- A short history of collection; this could be biographic or administrative and should be no more than a paragraph long.

- A summary of the contents of the collection: what kinds of materials it contains, for what dates, and covering what general topics.

- Restrictions on access and use of the collection, if there are any.

- The language (or languages) that are used in the collection.

- The preferred form of citation for the collection.

- A note linking this catalog record to the more extensive finding aid or register of contents.

- Electronic links to digitized parts of the collection and an electronic version of the finding aid.

- A list of subjects covered in the collection; these are topics and can be taken from subject heading lists such as the Library of Congress Subject Heading Authority File.

- The form/genre terms that apply to the collection such as Abstracts, Account books, Albums, Autobiographies, Census records, Clippings, Diaries, Genealogies, Government records, Interviews, Legal instruments, Maps, Military records, Receipts, Regimental histories, or Speeches. The Beinecke Library of Yale University has a good short list of terms. See Genre and Form Terms.

Here is an example of a catalog record for a collection held by the Cornell University Library. Notice that there is a prominent link to the finding aid for the collection.

Author/Creator: Kramer family. Title: Kramer family papers, 1939-2006. Description: 5.2 cubic ft. Electronic Access: Finding aid Biographical/Historical Note: Samuel Kramer of Ithaca, New York married Anne Gudis of Newark, New Jersey. Samuel served in the United States Army during World War II. Samuel and Anne had two sons, Kevin and Jeffrey, and a daughter, Michele. Kevin attended Cornell University and the Institute of European Studies in Vienna, Austria. Jeffrey earned a Master’s Degree in Hospital Administration from Cornell University in 1973. He served aboard the U.S.S. Nimitz at the time of the aborted rescue mission of the U.S. hostages in Iran in 1980. Summary: Family papers comprise correspondence and greeting cards, including letters written to the Kramer family from Kevin Kramer while in Vienna; pictures, letters, and diaries relating to Jeffrey A. Kramer’s service aboard the U.S.S. Nimitz; papers concerning Samuel Kramer’s World War II service; and Anne Gudis’ and Samuel’s war-time correspondence. Also, papers, research materials, notes, clippings, and correspondence relating to the history of the Ithaca Jewish community. Cite As: Kramer Family Papers, #3970. Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections, Cornell University Library. Subjects: Kramer, Anne G. Kramer, Jeffrey A. Kramer, Kevin Leslie. Kramer, Samuel J. Kramer family. Nimitz (Ship). Family --New York (State) --Ithaca. Iran Hostage Crisis, 1979-1981 --Personal narratives. Jews --New York (State) --Ithaca. World War, 1939-1945. Family --Virginia --Virginia Beach. Ithaca (N.Y.) --Religious life and customs. Photographs. Notes: Finding aid Finding Aids/Indexes: Folder listing. Location: Kroch Library Rare & Manuscripts (Non-Circulating) Call Number: Archives 3970 Database: Cornell University Library Link to this record: https://catalog.library.cornell.edu/cgi-bin/Pwebrecon.cgi?BBID=2070362&DB=local The Manual for Developing a Baptist Archives has a much shorter sample record in the form of a pair of catalog cards for an organizational archives: Catalog cards.

Once you have created a catalog record, you should prepare a finding aid for the collection. This is an inventory or register of contents. It typically has two elements: A full description of the collection as a whole and details about the contents of each container that is used to house it.

While the catalog record is kept as short as possible, finding aids can be quite long and detailed.

There are no standards for the structure or appearance of finding aids. You can design them to suit your own and your users' needs. The finding aid for the Kramer Family Papers is a good example of one.

Here is a table showing what they typically contain and showing where the information typically comes from:

Finding Aid Component

Where the Information Comes From

Creator(s) of collection

From the catalog record

Title of the collection

From the catalog record

Statement of Extent; the physical extent and condition of the collection

From the catalog record

Biographical Narrative/Administrative history

From your analysis of the collection; an expansion of the history paragraph on the catalog record

Scope and Content Statement

From your analysis of the collection; record what types of materials the collection contains, what dates, what sources

Statement of Organization

From your analysis of the collection; record the Order and structure of the collection; whether it is divided into sections (e.g., by type of material) and if so what

Statement of Arrangement

From your analysis of the collection; record the principle of organization that has been followed (e.g., chronological) and whether the original organization has been retained

Statement of Condition

From your analysis of the collection; record the physical extent and condition of materials in the collection

Restriction Information about use of the collection

From your data gathering; record administrative information about the collection; agreements, Copyright, etc.

Acquisition Information

From your data gathering; record administrative information on how the collection was obtained

Processing information

From the notes you have been taking about your work; record administrative information on who, when, and where the collection was processed

Conservation Information

From the notes you have been taking about your work; record information about preservation, housing, environmental conditions and the like

Container List

From the notes you have been taking about your work; record the order and structure of the collection

Access Points: Personal Names

From the catalog record

Access Points: Corporate Names

From the catalog record

Access Points: Geographic Names

From the catalog record

Access Points: Topical Subject Terms

From the catalog record

Access Points: Form and Genre Terms

From the catalog record

Access Points: Function Terms

From provenance information obtained while gathering information from internal and external sources

For further information on this topic see the Describing Archival Material section of the Manual for Small Archives and the Introduction to Metadata of the Getty Research Institute, and also see Links to sources on cataloging in the Resources section of this web page.

Protect, authenticate, appraise, and insure

Your storage area should have fire extinguishers and detectors for smoke and heat. To prevent against flooding, it should be located on an upper floor if possible. No boxes or any archival materials should be placed on the floor. Avoid locations with overhead water pipes. Take what precautions you can against whatever natural disasters your locale is subject to, such as hurricanes, tornados, and earthquakes. Make a plan for dealing with the collections in case of need to evacuate. Do not store all your backup and other copies in one place. Disperse them to at least two locations if you can. If you have any doubt about the authenticity of any item, consult a professional archivist. Make sure your insurance policy provides adequate coverage of your collections. Get a professional appraisal if necessary. Keep duplicate records about the collection in a separate location along with the copies you have made of the collection contents. Both door locks and alarms are desirable. The fire and police departments in many jurisdictions will conduct free inspections. Take advantage of these services if available.

Your storage area should have fire extinguishers and detectors for smoke and heat. To prevent against flooding, it should be located on an upper floor if possible. No boxes or any archival materials should be placed on the floor. Avoid locations with overhead water pipes. Take what precautions you can against whatever natural disasters your locale is subject to, such as hurricanes, tornados, and earthquakes. Make a plan for dealing with the collections in case of need to evacuate. Do not store all your backup and other copies in one place. Disperse them to at least two locations if you can. If you have any doubt about the authenticity of any item, consult a professional archivist. Make sure your insurance policy provides adequate coverage of your collections. Get a professional appraisal if necessary. Keep duplicate records about the collection in a separate location along with the copies you have made of the collection contents. Both door locks and alarms are desirable. The fire and police departments in many jurisdictions will conduct free inspections. Take advantage of these services if available.For more information on this topic see:

- Disaster Planning and Recovery, Chapter 5 of the Canadian Council on Archives handbook, Basic Conservation of Archival Materials (also known as the Red Book)

- Preserving Your Family Treasures from the Library of Congress

- The Emergency Management section of the Preservation Leaflets series of the Northeast Document Conservation Center, including:

- Protection from Loss: Water and Fire Damage, Biological Agents, Theft, and Vandalism

- An Introduction to Fire Detection, Alarm, and Automatic Fire Sprinklers

- Disaster Planning

- Worksheet for Outlining a Disaster Plan

- Emergency Management Bibliography

- Emergency Salvage of Wet Books and Records

- Emergency Salvage of Wet Photographs

- Emergency Salvage of Moldy Books and Paper

- Collections Security: Planning and Prevention for Libraries and Archives

Establish a digital preservation program

This section deals with archival materials in digital formats, but not with the preservation of web sites. For help on that subject see A Guide for Archiving Web Pages, in another section of these pages.

This section deals with archival materials in digital formats, but not with the preservation of web sites. For help on that subject see A Guide for Archiving Web Pages, in another section of these pages.A digital preservation program addresses both electronic media (the hardware and software used for presenting electronic content) and the content itself. Since neither component is inherently long-lived and since content can usually be copied without loss of fidelity, preservation is achieved by replication. A replication plan must recognize that media quite quickly become obsolete and thus content must either be copied onto new media -- ones that are currently in use -- or copied onto more durable media (for example an online textual document might be printed out on durable and permanent paper stock).

Although the number and complexity of both media and formats of content generally cause the larger preservation programs to be complex and expensive, small programs can be manageable for individuals and small archives.

The contents of digital collections may be either acquired from external sources or produced locally. They may have been derived from other content (e.g., via scanning) or they may have been created digitally in the first instance.

The contents may exist in any of a large number of formats. Examples of prominent file formats include BMP, CSV, DOC, DOCX, GIF, JPEG (.jpg or .jpeg), JS, MOV, MP3, MPEG (.mpeg, .mpg), PDF, PHP, PPT, RSS, TIFF (.tif or .tiff), and XLS. The Library of Congress has a set of web pages giving information on the usefulness of each format in the preservation context -- the term used is sustainability rather than longevity because they all lack inherent permanence.

Many of the tasks associated with non-digital collections also apply to digital ones. You should create a program plan, keep good records about the collection and the actions you take respecting it, learn as much as you can about the collection and its contents, understand preservation needs (in this case mostly replicability), create a catalog record and finding aid (in this case generally called metadata), and consider whether and how you wish to make the collection accessible to others.

In many cases you will wish to establish an explicit collection development policy, that is a statement (a) laying out what pertains to the collection and what does not and (b) recording your intentions regarding the collection's growth over time (if it will grow).

If the collection is to be made accessible via the Internet, there should be no barriers to access by people with disabilities, it should violate no intellectual property rights or rights of privacy, and it should be formatted so that it can be migrated to new media as they supplant existing ones.

A digital preservation program should recognize that people with necessary expertise, commitment, and resources will be needed to perpetuate the collection into the future.

These and other related actions are summarized in Digital Preservation, Part 8 of a tutorial by the Research Department of Cornell University Library and in an overview presented by the National Information Standards Organization called A Framework of Guidance for Building Good Digital Collections .

Other useful resources include:-

Engaging online education: Mastering digital archives, Presentation at the Society of American Archivists Meeting SAA Annual Meeting, New Orleans 2013

- Creating and Managing Digital Content by the Canadian Heritage Information Network

- The Exploring Digitization segment of the Preservation 101 tutorial from the Northeast Document Conservation Center

- Digital Preservation Management: Implementing Short-term strategies for Long-term problems, a tutorial developed by Cornell University Library.

Also see the Links to sources on digital preservation in the Resources section of this web page.

Home >>