By Arthur D. Hettema

Chief Carpenter's Mate

Sea Bees

World War II

A True Story

Dedicated To My Wife

Adeline

(Self published, 1985)

Chapter One

Camp Perry

All I knew about demolition at Camp Perry, Virginia, was that every so often I could hear the thunderous detonations of explosives which even rattled the windows of the barracks. We also heard, 'round and about, that the training here for Navy Combat Demolition Units was rough and tough. The Marines who did the training thought nothing of ordering twelve-mile hikes with part of them done at double time. If you couldn't keep up, you could get out of this physical endurance which was required day after day.

It was on September 21, 1943, at Indianapolis, Indiana that I enlisted in the Sea Bees. World War II was in full swing. I was 35 years old and given the rank of Chief Carpenter's Mate because of my background: a civil engineer and superintendent of construction for Hagerman Construction Corporation, Fort Wayne.

I was sent immediately to Camp Perry. Here with many other Chiefs, we were instructed in combat duty just as were the Marines who were also stationed here. We learned how to handle the enemy, how to protect a camp and men, how to advance against the enemy and how to set up a perimeter guard, among other things.

After about three months of this training, we Chiefs became bored. It all seemed tedious and uninteresting. One afternoon Tom McKnight from California and one of the Chiefs at the camp, came over to my barracks and explained to a group of us what a terrific deal it would be to volunteer for a Demolition Team. He went to great lengths to tell us what he knew, emphasizing that we'd get a 10-day leave immediately, or, if we'd rather, we could go to Washington, D.C. for bomb disposal training for 30 days and a chance to live off base.

Right then and there Tom and I volunteered and shortly our wives joined us in Washington. We had 30 great days living in rented rooms. We were given $5 a day subsistence which meant we could eat out every night. A big treat. Tom and I ate breakfast and lunch at the commissary on the base.

We were trained at the Mine Disposal School here in Washington learning how to dismantle both German and Japanese bombs by removing the detonators. With this knowledge, we could defuse a mine which might be up against a ship or dock and which, of course, must be disarmed before it could be moved. We learned that the most difficult mine to defuse was the acoustic mine

1

invented by the Germans. If you made the slightest noise while removing the detonator, th mine would explode. If, while training, we did make a mistake, a red light flashed on showing us we'd failed to remove the detonator correctly.

Thirteen Chiefs took this training - all of us trained to defuse mines in a combat zone - all learning that the best method to blow a mine was to attach a two-pound sack of Composition C to the mine.

When the 30-days' training was over, Tom and I, as well as the other Chiefs who had been there, went to Fort Pierce, Florida to then begin our amphibious training.

2

Chapter Two

Fort Pierce

Fort Pierce was the birthplace of Frogmen, later called SEALS, the Navy's secret weapon.

It was a huge training center, the only Underwater Demolition Training Center during World War II. Our preliminary training took place on Hutchinson Islands. These Islands are north of Fort Pierce, just far enough away from residents so no one was shaken up by the explosives we set off daily. I remember, though, some of us blew some rock out of a channel at Stuart, 20 miles south of us, and windows in some of the stores were broken.

At Fort Pierce instead of combat units, we were organized into a team of 113 men with a Chief and Officer for each platoon. By the time we finished our training here, we had four platoons. We became Underwater Teams and these Teams were made up of 50 champion swimmers from various colleges around the country all training for similar tasks such as we were training. These 50 swimmers were distributed among the U.W. Teams. One of these swimmers was breast-stroke swimming champion at Yale University. Another was William Hopper, son of famed columnist, Hedda Hopper.

With T.N.T. and half-pound blocks of T.N.T. why, we could blow up a half mile of obstacles such as concrete pyramids, jetted pilings, English scaffolding, barbed wire and mines, if necessary. We could make a channel through a coral reef with the use of tetratal packs laid two feet apart with a row of rubber hoses filled with T.N.T. on each side of the width of the channel - a total of 10 tons of explosives. The large center portion was blown first and seconds later, with delayed caps, the rubber hose went off. This then threw the coral out of the new channel. After the obstacles were out of the way, the Marines or Army could land troops on the beach without any obstructions.

My Officer, J.J. Jackson and I capped off our section of the beach at Hutchinson Island. We carried the waterproofed caps in the pocket of our swim trunks. After the primacord was connected to all the obstacles, we'd withdraw. Then after we capped off the primacord in two places, we swam back to the landing craft where we proceeded to set off the charge with a hell box connected to a

3

wire cable which was attached to electric caps. The entire operation took approximately 30 minutes and this meant setting off the whole line of obstacles at one time. There were 10 of us swimmers from each team who completed this operation.

The crew for one landing craft consisted of the following: one port gunner, starboard and stern gunners, a coxswain, two radio men, a photographer, a pickup man and 10 swimmers. The landing craft we used was the same as those Marines used to reach the beaches. This boat had a wooden hull and was built low to the water making it easy for us to jump out. The motor was powerful enough to produce 21 knots an hour. We'd always crouch down low enough so we weren't visible. The only person exposed was the coxswain who stood at the wheel.

Later on in the War, we were assigned to Attack Personnel Destroyers equipped with two landing craft on davits placed on each side of the ship's deck. These Destroyers had troop compartments on the main deck. The ship had a complement of about 300 sailors who actually ran the ship while our men helped in the mess hall and helped keep the ship clean. The Captain of the Destroyers held the rank of Lieutenant Senior Grade. We learned our Captain's family owned Macy's Department Store in New York. The Officer in command of our team was Lt. Commander Brooks from Texas. I was always a strong swimmer having been brought up on Cranberry Lake in New Jersey. Often my brother and I would swim the length of this Lake just for the fun of it. While attending Tri-State Engineering College, Indiana, I was a member of the swim team and winner of several trophies.

4

Chapter Three

San Francisco and

Maui

Our training completed at Fort Pierce, a troop train transported us from here to San Francisco. It took five days. Why this long? Because the government used all government-owned railroads they possibly could. The three weeks in San Francisco before we were shipped to the Hawaiian Islands, all Chiefs were given leave every day if we had enough money for fare into the city. It was terrific. I spent my three weeks' evenings' at the Mark Hopkins, Sir Francis Drake and Fairmont Hotel lounges.

While we were still in San Francisco, one of the young sailors in our team found a stray female dog which he smuggled onto the ship. We named her Esther and even got permission from our commanding officer to take her with us on the U.S.S. Blessman and into combat. She was our mascot and we all loved her. Esther was probably the only dog which went through the war. But there's more about this beloved mutt: She was injured at Iwo Jima and when we received our medals later on at Maui, she was given a Purple Heart.

Finally we were shipped to our Advance Base which was Maui.

Needing every ship possible, we boarded, at San Francisco, a Dutch ship with a Javanese crew and Dutch officers. They let us off at Honolulu where a Navy boat took us to Maui.

I was in Team 15 and Tom McKnight was in Team 10. More rigorous training was scheduled for us in the Pacific. We'd swim a triangular course for one mile every day before lunch. In the afternoon, we swam to beaches, often over coral reefs which were close to the surface, making it necessary for us to crawl across them. At night we practiced hitting the beaches in the dark. The pinpoint flashlights tied around our necks we'd flash for picking up by our landing crafts.

The Pacific Ocean here was extremely clear. We oftentimes could see that we were swimming over good-size sharks. It was emphatically drilled into us to keep our arms and legs under the water so no splashes would be detected by the enemy or by sharks.

In order that we become accustomed to all sorts of situations, we swimmers were taken to a rugged beach on which there was a cliff on one side and 10-foot wave action.

5

One night our Attack Personnel Destroyer, the U.S.S. Blessman, 300-feet in length and 35-feet wide, anchored about a thousand yards off the shoreline and dropped us off in our landing crafts. From these we tumbled into the water in pairs. We always swam in pairs. Each of us wore trunks, a sheath knife, face mask, pin-point flashlight, waterproof watch and a belt-type life preserver. Our dog tags were around our necks.

My swim-partner, Ron Ravanholt, six feet, 2 inches tall, known as the Big Dane from Montana, and I, swam in toward the beach. When we heard the waves pounding on the beach, we began looking around for man-made objects or obstacles. At the same time we kept our eyes peeled for coral reefs which would prevent a Marine landing craft from reaching the shore in the event of an invasion.

As we swam toward the breaker line, suddenly a huge wave catapulted me right smack up onto the beach. This, certainly, was a no-no. We'd been trained not to let this very thing happen for, for sure, we'd attract the enemy and so be promptly captured. My instinct made me dive back under another huge wave, kick for all was worth so I could get through the second and third waves and on out beyond the wave action. Buddy Ravanholt had also been thrown onto the beach and was nowhere in my sight. I was just getting my breath back and my wits about me when I could feel something clinging to my neck. I knew it must be a Japanese Mano-War. It was. A little purple dirigible type balloon with hundreds of string-like tentacles hanging down and each capable of paralyzing whatever it would touch. I quickly dragged it down my arm and off my fingertips. My entire left side was, in this short time, paralyzed. I couldn't use my arm nor my leg. I kept telling myself I must keep moving away from the beach so I blew up only one section of my life preserver and with my right arm and leg I managed to move ahead ever so slowly. I knew I had to swim at least 700 yards to the Destroyer Blessman. I was alone and extremely apprehensive. Could I make it in the heavy seas? Suddenly, there was a splash and, miracle of miracles, Ravanholt appeared by my side. I told him what had happened and he began to rub my paralyzed arm and leg. This did help. I could swim a little. Every so often we'd tread water and he'd hold his flashlight above his head, flashing it on and off, hoping someone on the Destroyer would spot us.

It was two hours before our landing craft, which had been searching and searching for us, finally saw us. We were picked up and taken back to the Blessman. I limped onto the deck and went directly to sick bay where the pharmacist rubbed my arm and leg with a soothing solution. For a couple of days I continued to limp around and my arm looked like barbed wire had been dragged all

6

the way down it. Let me tell you, from then on I had great respect for the little Man-o-War.

The biggest charge we set off at Maui was 20 tons. It was supposed to make a channel for the Marines stationed at a neighboring base. This charge almost blew their tents away and loads of fish and large eels came to the surface. Some charge!

In our Unit there were 113 men to a team including 13 officers and 10 Chiefs. We were assigned to an Attack Personnel Destroyer with four landing crafts, four rubber rafts and a troop compartment for us men. We worked as a Platoon: one Officer and one Chief for each Platoon. Those of us who were swimmers always swam in pairs as we'd been trained and always left the landing craft at one thousand yards out. Always, once again, we wore swim trunks, a Navy knife, waterproof watch, face mask, dog tags and a plex-aglass slate fastened to our leg with a pencil attached so we could write down a brief description of the beach line and gun emplacements. As you must realize, we were a highly trained group and physically fit for strenuous combat duty.

The Sea Bees here on Maui built a Chief's room on a beautiful bay with the view of the ocean unmatched anywhere. We'd drink our beer and have a snack, as our mood indicated. As a matter of fact, every base I went to they had their own club rooms and even on board ship we had separate rooms where we'd play cards or get sandwiches from a refrigerator always well stocked.

When I received a day's leave, I'd hike to Lahania, an old whaling town. Often we saw whales spouting and could even see their enormous size. There was one bar in town and, of course, the only way to pass time was to sit here and enjoy our beer. Leave ended at six o'clock so we made sure we were back to our Base by that time.

7

Chapter Four

U.S.S. Blessman

Eniwetok and

Babelthuap

We left Pearl Harbor on December 10, 1944, on the Attack Personnel Destroyer, U.S.S. Blessman, recently converted from a Destroyer Escort having been in the European theatre of war.

Our sister ship, the U.S.S. Bull, A.P.D., accompanied us on our way out to combat in the Pacific. We were all excited to be on our way "down under." We were headed for Eniwetok, one of the Marshall Islands, south of Hawaii and several hundred miles east of the Philippines. It is 100 miles north of the Equator.

Our first scare came when the weird and terrifying sound of the general alarm went off calling all of us to general headquarters and to our battle stations. Every sailor was assigned to man a specific station and gun positions at general headquarters. It turned out that our sister ship, U.S.S. Bull, thought it had picked up sound contact with an enemy submarine. But, thank goodness, nothing happened. The rest of the trip to Eniwetok was uneventful.

The number of U.S. warships anchored in the bay at Eniwetok amazed us. There were a great many. The Island itself looked as if thousands of masts were sticking up out of the ground. These were, we learned, trunks of palm trees with all the fronds shot off by our Marines. When they'd recaptured the Island from the Japanese, they discovered Jap snipers in the fronds and proceeded to eliminate them.

I was one of the lucky guys to go ashore on Christmas Day. We were all given two cans of beer. Admiral Nimitz had given his approval. He was there on the Island. But, we hadn't been there very long when we were ordered back to the Ship. Shortly after our return, we took off for Saipan, north of our route, to escort a P.A. which was carrying parts needed for the B-29s which were bombing Japan.

We let off the Liberty Ship and continued on our way to Babelthuap and we rendezvoused at the Palua Islands with the other five Underwater Demolition Teams. Here we stayed at anchor for five days. We had a great time visiting members of the other teams with whom we'd trained. I visited Chief Tom McKnight on his Attack Personnel Destroyer. We sat on his bunk and talked. He was a bit unhappy because he wasn't ever allowed to leave his Destroyer at any time. It was wonderful to see him again and it was to be the

8

last time I'd ever see him. Our visit was cut short. We were called back to our ship for briefing on the part we were to play in the invasion of Luzon in the Philippines. Just a note: 28,000 Japanese were left stranded at Babelthuap - they had no rescuers.

As we left Babelthuap, we were in battle formation and mighty glad to have so many aircraft carriers, battleships, cruisers and destroyers accompanying us. The destroyers were in front and back and on both sides. They could destroy any enemy submarines and with their radar guns knock down enemy planes at night.

We passed Leyte which the Army had already secured and continued through the Mindanau Sea just as darkness was setting in. Because the Japs occupied both sides of Mindanau Straits, we made a run through getting to the Zula Sea around daybreak. Going through the Straits, we decided to stay up and play black jack. This was New Year's Eve, December 31, 1944. Several Chiefs and Officers were in the game held in the Chiefs' quarters. We played ten dollars a card. When you were banker and dealer, it took at least $200 to handle the deal. We played a while and then coaxed the chief pharmacist to get a gallon of medicinal alcohol from sick bay. After we drank this, with lemonade, we talked the demolition chief into getting a box of two-ounce bottles of brandy from his supply room. Both Chiefs were later reprimanded by the Captain for taking supplies without permission. Well, I went broke several times during the evening and each time Lt. J.J. Jackson loaned me a stake so I could stay in the game. His folks owned two taverns in Newark, New Jersey and he received money every month from them in addition to his Navy pay. At daybreak Jap suicide planes began to zero in on us so we quit the game and went to man the guns and protect ourselves from a direct hit by the Japs.

Finally, I hit the sack, around 11 o'clock I guess, but hadn't slept long before the alarm went off again, probably around midnight. The Japs were up there trying to find a target.

The next day we were in the China Sea where there was more space for us to spread out. But, continually, Jap suicide planes attacked. These we were able to destroy with a heavy barrage of flak.

9

Chapter Five

Lingayen Gulf - Luzon Invasion

On the evening of January 5, 1945, we reached the entrance to Lingayen Gulf. Forty some mine sweepers were already clearing the entrance. On January 6, our battleships and cruisers bombarded the shorelines on both sides. By noontime the minesweeps had swept a channel right down the middle so we could go along down the Gulf.

Up to this time, we'd been attacked by single planes. The U.S.S. Blessman had had orders to hold her fire and let the larger ships do the job. We got pretty well down the Gulf, had just turned about face to proceed out. when all hell broke loose. A steady stream of Jap planes came in low over the mountains attacking us from both sides. It looked mighty serious for us, that's for sure. All our guns were firing - the Blessman was firing for its life for the first time. We served evening chow to the men right at their battle stations and we kept carrying ammunition to them way into the evening.

We did make it out of the Gulf safely but everyone of us was mighty concerned about going back through the next morning. Several of the biggest ships had taken direct hits from these Jap kamikaze suicide planes. Our command ship had lost about 35 men and the bridge had been torn off. No ships were sunk although super structures were badly damaged.

One Jap plane flew just above the water trying for all it was worth to keep under our radar. I was on the starboard side of the ship when this plane passed about 30-feet away. It banked right over our fantail and hit the cruiser California on its bridge. Then, this plane, exploded. Our 20 and 40 millimeter guns were following it as it flew by and sadly, accidentally shot into the side of the California. A few minutes prior to the Portland being hit it was necessary for the Blessman as well as the California to try to dodge 25 or 30 sailors who had been thrown into the water. We were told that several other ships had been hit. Nonetheless, our destroyers with their radar guns had succeeded in knocking down quite a few Jap planes.

During the night, we were attacked several times by more Jap suicide planes but still our guns kept knocking them down.

The next day was Sunday, January 7, 1945, two days before D-Day - every invasion in the Pacific was called D-Day. We were scheduled to make our approach to the beaches that day to prepare and clear them for MacArthur's men to make a landing.

10

At daybreak we were already on our way back up the Gulf of Lingayen. We'd been given orders to go in at 1000 hours. But, up to that time, the beaches had been shelled lightly. Our pre-assault was postponed until two o'clock thus giving us the advantage of four more hours of heavy bombardment so as to clear an area from the beaches to a distance of six miles inland.

I'll tell you, I was plenty nervous because of the delay although, I must admit, I got up that morning feeling just swell and anxious to get it over with. Finally, there we were, we Frogmen, crouched down in the Personnel landing craft. I truly felt quite relaxed. Taking part in this Luzon invasion from our platoon were these swimmers in pairs: Lieutenant Jackson and Richards (Able), Wildfong and Bailey (Baker), Andrews and Monroe Fox (Charlie), Chief Hettema and Ravanholt (Dog) and MacCallum and Shroyer (Easy). Able, Baker, Charlie, Dog and Easy were Navy code names. Also there were swimmers from each of the other five teams.

Well, we proceeded toward the beaches. Near the 500-yard position, we swimmers, in pairs and 15 yards apart, dropped into the water. Ravanholt and I were soon swimming toward this enemy beach. As always, we had on bathing trunks, flippers, a plex-a-glass 5 x 12 slate with pencil attached to our right leg, a Navy knife, waterproof watch, dog tags and face masks. We'd been instructed that as we got into 10-feet depth of water we should make numerous surface dives to try to find cables attached to electric bombs which could be set off from the shore by the Japs. We were very careful to keep our hands and legs under the water so as not to be noticed from the shore. We took in air at the bottom of the swell and stayed under at the top of the swell. No way did we want to give the sharpshooters on the beach anything to aim at. Odd as it may seem, the Jap's defense of the beaches had included no obstacles to stop an invasion. We swam up to the breaker line and made notations on our slates as to breaker action, gun emplacements, height of the beach and any object in the way of our Army's tanks. We figured the Japs undoubtedly thought it was difficult to land there because of the 10 to 15-feet wave action which would probably throw the landing craft sideways and out of control thereby bottling up the invasion.

We swam back to our landing crafts and were soon back aboard the Blessman. I changed into dry clothes after taking a shower, downed six ounces of brandy and was then ready to consume a decent evening meal.

Enemy planes tried to get in at us at seven o'clock that evening and then once again around midnight. They had little or no success.

Monday we were attacked very few times because our fighter

11

planes were doing such a tremendous job intercepting them before they even reached us. We kept cruising back and forth waiting for the Army transports to arrive.

Tuesday, the Big Day, D-Day, the Gulf was cram-packed with transports, L.S. Ts, L.C. Ss, plus other types of craft. We tied up along side the supply ship, Rickey Mount, a risky maneuver indeed. For better than an hour, we were fastened together by the fuel hose refilling our tanks. The Army was loading troops onto the landing craft and the L.S. Ts were disgorging amphibious tanks from their bowels. L.S. Cs were slid off the decks and with the amphibs leading, the invasion got underway at 9 o'clock. Each succeeding wave of equipment and men made the beach safely.

Before too long, the amphibious tanks had penetrated six miles inland. What a sight to watch the landing crafts shuttle back and forth carrying men, tanks, jeeps, bulldozers - the equipment needed to supply an army. L.C. Cs carried in the tanks and dozers, simply opening their fronts for the equipment to land. With the 10-feet waves, several of the crafts broached sideways making it necessary for salvage ships to pull them out of the way. This they managed with the use of cables.

During the afternoon, several of our officers went onto the beaches but none of us men could go in. They brought back dozens of life preservers which we badly needed.

All through the night planes kept attacking us. Toward morning, Jap swimmers attached mines to the sides of some of our ships. Before sunrise, U.S. Navy searchlights were hunting for these Jap frogmen. Because of all the debris in the water, it was impossible to spot any of them.

12

Chapter Six

Convoy

Leyte and Samar

On the afternoon of January 10, we were asked to blow a path in a nearby river so the Army could unload supplies without having their crafts capsize. We used tetratal and rubber hoses to blow this underwater channel. But, around five o'clock, we were called back to the Blessman. We'd received orders to leave with a convoy of empty ships, mostly transports, going back for more supplies. We had to leave four men on the beach. We simply couldn't wait for them.

We were now escorting, and hopefully protecting, 36 transports and eight destroyers. A few times our radar picked up enemy planes but they were scared off by our fighter planes. Back through the Mindanau Sea we went and did reach Leyte safely.

At Leyte, we heard that the day after we left Lingayen Gulf, Team Ten's ship had been hit by a suicide plane sweeping three men off the top landing craft of the ship. Naturally, I was anxious to hear whether or not Chief Tom McKnight was safe. He was manning a 50-caliber machine gun on one of the crafts at that time. It really wasn't part of his job to man a gun but that was Tom for you. Always dedicated, always anxious to do more than was required of him. We later heard that the landing craft on which he had been, was swept overboard and two other crew members went too. The two came to the surface and were rescued but not Tom. Apparently he was trapped with the landing craft on top of him. He was reported missing in action. When the war was over, his widow came to my home in Indiana to hear my account of what had happened and to assure herself he had drowned in Lingayen Gulf. One of the Chiefs on his ship, Chief Russell, verified the account of his death.

We anchored off the shore of Samar and the Captain of our ship gave us 45 minutes' shore leave and two cans of beer a piece. I walked up into the nearby Philippine village and could scarcely believe what I saw. The natives were living in thatched huts, one right up against the other. There was no privacy for anyone. There were no windows, just openings for doors and no furniture at all. The framework of these huts was made of small logs and the sides and openings were of woven reeds. They had no toilet facilities - they simply used the streets.

13

The men in this village had fenced in an area about three feet high and it was here cockfights were being held. We watched a fight and could see some kind of bets being made.

We noticed everyone was barefooted. The men wore shirts and trousers acquired from the U.S. Army. Most of the women had on white dresses which, we concluded, were copied from styles in a Sears Roebuck catalog.

On the beach, we saw equipment left behind after the invasion of Leyte. There were lots of large wooden boxes still unopened. A nineyear-old Filipino boy came up to us and kept pointing to the boxes. He made us understand he wanted us to open one of them. We did. We pried off the top and found it filled with Army shoes of all sizes. We each took a couple of pairs. We would cut them up for open sandals. The little boy took a couple of pairs and then sat on my lap and sang, "Oh, Johnny. Oh, Johnny. How I love you." One of our photographers took a picture of me sitting on the box and the boy on my lap.

14

Our allotted 45 minutes was up. We got into our landing crafts and went back to our ship.

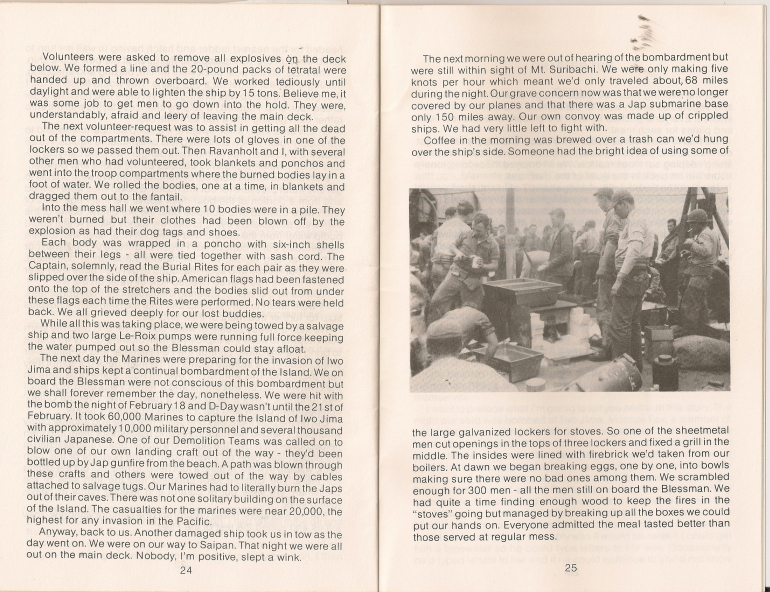

Every day, anchored off Samar, we were visited by native families in their outrigger canoes, carved from trunks of trees, very crude but serving their purpose well. The father, mother, boys and girls and banty roosters came out to the ship all in one outrigger.

The women wanted white mattress covers for making dresses, the young women made their dresses from Navy sheets and patterned them after fashions copied from Sears Roebuck Catalogs. The Corner Grocery store on Samar was a favorite gathering place for the Filipino girls. The men wanted Navy fatigue trousers they could cut off for shorts. We traded Navy sheets for colored woven mats designed with an American eagle or U.S.A. or Victory with the Philippine country in '45 - souvenirs for us to take home with us.

We stayed there for an additional five days playing water polo alongside the ship. Movies were shown on the fantail but the third night this had to stop as Jap planes were out raiding. The entire ship was blacked-out.

15

Chapter Seven

Ulithi

Without receiving our mail, we left Samar and headed for Ulithi approximately 900 miles north. At the entrance to the large bay, the submarine nets were opened and we entered. We were mighty glad, and proud, to see so many of our warships anchored in there. Our U.S. Navy was at full strength with battleships, cruisers, air craft carriers and lots of destroyers.

Our pre-assault force included six Attack Personnel Destroyers with each one carrying a complement of 130 men and officers.

As for the Swimmers, or the Frogmen, we were required to wear, as we always did, bathing trunks, plus a belt-type life preserver with two compartments containing C02 cylinders which could be released with one hand if perchance we were wounded. Otherwise, there were two rubber hoses which we could reach with our mouth and blow up. We never did inflate them while swimming because they then became a hindrance. We saved them for an emergency.

We anchored off a small uninhabited island which was literally covered with coconut trees. Some of us were allowed to go ashore with the usual ration of two cans of beer. I suggested to officer Lieutenant J.J. Jackson that we make a picnic of it. Okay. So, we got hold of some ham, pickles and cheese from the commissary. There on the beach we went swimming and hunted for cats' paws and other beautiful shells we could make into rings. We were supposed to have all day on the beach but, without explanation, we were called back to our ship and were ordered to stand at attention. We were questioned concerning two turkeys which were missing from the freezer locker. It seems, our Captain had a date with an Army nurse at Leyte. He was going to give them to her as a special gift. She hadn't eaten turkey since leaving the States. But he was jilted by the nurse and came back to the ship bringing the two turkeys with him. It was announced later that the birds were found in back of some boxes. We were dismissed but we had lost our day on the beach.

However, while we were enjoying our brief respite on the beach it seems officers on our ship, and from other ships in the area had a big crap game going. Lieutenant J. J. Jackson told me some time later he won several hundred dollars. I surmise there was a lot of drinking at game-time as well.

16

After all this time our mail caught up with us. Because of the invasion of the Philippines it had been held up. Since Demolition was a secretive outfit, we never got our mail when the others did. Anyway, we were mighty happy to get it. It was, of course, an excellent morale builder.

Here at Ulithi we were briefed on the pre-assault invasion of Iwo Jima. U.S. Army planes from Saipan had bombed the Island for 68 straight days. We carefully studied photographs of every single bombing. In the beginning, we could see there had been some small buildings there but soon they disappeared. During the last few days of the bombing, numerous barrels were set along the beach. We figured maybe they had fuel oil in them and so could be set afire with the flames covering the water and engulfing us Frogmen as we swam into the beach. We guessed they had been used by the Japs to pinpoint guns allowing them to cover the entire beach with their gunfire.

*On Cover - Picture was taken on the Island of Ulithi - Feb. 6, 1945

17

Chapter Eight

Iwo Jima

On the tenth day of February, 1945, we pulled anchor and were on our way to what we knew would be our toughest job to date in the Pacific.

The reason for wanting to capture Iwo Jima was this: it was 700 miles from Tokyo and from here the Japs were putting up fighter planes from the three airstrips thus making it possible for them to shoot down our B29s as we flew over on our way to bomb Tokyo.

We reached Saipan and maneuvered off the Island just killing time. We wanted to make a fast run in, reaching there at daybreak when the Third Fleet air carriers were scheduled to bomb Tokyo. We were with the Fifth and Seventh Fleets so we had plenty of fire power. Over the horizon at our stern, at times we could barely make out the super structures of the aircraft carriers. But, we were told, the amount of air coverage was tremendous. Besides the Navy aircraft, we had the support of the Marine aircraft and, additionally, Army bombers from Saipan. We were keeping our fingers crossed in hopes the Jap suicide planes wouldn't be as bad as they had been at Lingayen Gulf.

At daybreak, February 17, we were within sight of an Island of rock called Iwo Jima. Mt. Suribachi stood out prominently as did the cliffs on the north side of the Island. It was cloudy that morning, ominous, making it hard to spot enemy planes. The battleships and cruisers went in to bomb the Island using everything from five-inch to 16-inch shells. Our planes destroyed what was left of the Japanese planes on the airstrips. Those that did make it into the air were shot down by our destroyers. The little minesweeps were in close to shore doing a heroic job of clearing the mines from the approaches to the beach. It looked to us from seaward-side that they were right up against the shore. Every so often they were fired on by the Japs and immediately our battleships answered with some mighty big shells. When they did fire their guns, we could locate their positions and let our guns loose on them.

During the afternoon, our Captain announced all our warships would make a run around the Island to take a closer look. It didn't take us long to make one circle - the Island was only five and onehalf miles long and one and one-half miles wide at its widest part. We felt confident because we encountered very little heavy gun fire

18

from the shores. The Japs, devious as they were, held back their fire so as not to give away their gun positions before the invasion of our troops.

That evening we withdrew to positions on the outer screen. We listened to planes overhead trying to locate us. Once again we were briefed on our job for the next day. My platoon was scheduled to go in to the eastern beach as standbys. In the afternoon, we would go in on the western beach making the Japs defend both beaches. Believe me, I didn't relish the idea of swimming into that awesome little pile of rocks. No way. But you certainly can't refuse a military order.

Our Team 15 consisted of boat officer, Lieutenant Brooks; port gunner, Peterson; starboard gunner, Davis; coxswain, Vanda walker; stern gunner, Gordan; radiomen, Emmons and Riordan; photographer and swimmer pickup man, Shroyer. Swimmers were Lieutenant Jackson and Richards, Wildfong and Sanford, MacCullum and Bailey, May and Monroe Fox, Hettema and Ravanholt.

Things were just too quiet the next morning, especially the lull in the bombardment. We had bombed Iwo Jima all night long, enough to keep the Japs in their caves. At 10:30, we left our Attack Personnel Destroyers. In our landing crafts we proceeded to the eastern beach. Our position was just in back of the eleven L. C. I. gunboats and in front of the battleships, cruisers and destroyers. The gigantic shells whistling over our heads didn't make us feel very comfortable - every so often one would burst prematurely. Terrifying!

At 11 o'clock, all hell did break loose and the eleven L. C. Is lined up in the front line were destroyed by the Jap shore guns. We could hear men screaming for doctors. We could see the gunboats capsizing and sinking. We were a standby boat waiting to see if the other Demolition Teams were successful in removing obstacles to the beach. We couldn't see our P.L.s the smoke was so thick from the dastardly duel of guns. Although it was, overhead, a clear day, the sun was completely blotted out by smoke from the guns.

For one and one-half hours, I watched. I was seeing the most nerveracking and horrible sight I had ever witnessed. I was completely and absolutely exhausted when I reached our ship. I couldn't eat a speck of chow. I knew, too, it was smarter to swim in at 1 o'clock on a practically empty stomach. I prepared as best I could for the afternoon assault. Outwardly I probably seemed cool, calm and collected, but inwardly I was in a turmoil - everything inside me was churning. I lay in a rubber boat which we used for recovery of swimmers. I knew I must relax. As the time drew near, we still had not left the ship to take our positions. Naturally down deep, we were all hoping the operation would be called off.

19

At 3'clock, our Executive Officer announced that the operation would be delayed one hour and that, and our hearts sunk, we would not have the support of the L.C.I. gunboats. They'd been damaged most of them had sunk. Oh, what a let down. We counted on these boats to give us fire support directly on the beach thus keeping Jap sharpshooters from taking a shot at us in the water. Well, as they say, what's to worry. If I were to die. I sure couldn't prevent it by worrying.

Next we were told this delay would allow fighter planes to arrive from Saipan. They'd give us fire support on the beach. We were all wearing our waterproof watches and we synchronized them carefully. Our maneuver had to be a well-timed assault.

We left our Attack Personnel Destroyers and headed toward the beach near Mt. Suribachi. Motar shells were dropping all around us - front, back, sides. Fortunately, though, none on us. It seemed an endless ride into the position assigned us. All six Underwater Demolition Teams were to participate. Just as we reached the designated yardage from the beach where the swimmers were to be dropped off, one of our planes laid a smoke screen the entire length of the beach giving us a chance to start off in pairs without being seen by the enemy. For the next hour, plane after plane strafed the western beach at Iwo Jima. We were certainly given excellent fire support.

Ravanholt and I were the last swimmers dumped out of our landing craft. We started swimming toward the beach. Needless to say, we remembered our training well and kept under the water at the top of the swell and took air at the bottom of the swell. We could see the gun emplacements on the beach and took note of the swell. Too, we noted the height of the sand and the height of the breakers. All this information we jotted down on our slates, always fastened as I've said, to our right leg.

Both my buddy Ravanholt and I were in our usual good form and swimming strongly. After several surface dives to look for possible electric cables connected to mines, we swam to the breaker line. Actually, I guess you'd say we were human mine sweepers. We, at the same time, determined there were no coral reefs to hinder the amphibious tanks from reaching the beach. Our mission accomplished. we began swimming out beyond range of rifle and mortar fire where we could be picked up by our landing craft.

We could see our craft picking up the swimmers who'd been dropped off first. But, we were dismayed to see it turn and go back from the end of the line. We tried to remain stationary in the water. we'd tread the water when our craft came near and tried, over and over, in vain, to signal them every time we were at the top of a swell. We

20

didn't panic, just hoped and prayed. They were in closer to shore than we were and had no idea where we might be. Being strong swimmers, we were further out than they realized. There was a small island in front of us and Ravanholt and I concluded we'd have to swim around it, or what else? Yes, be taken prisoners by the Japs. The other option was to continue swimming another mile to the ships.

It seems the officer in charge of our platoon, although he'd been told not to sacrifice the men they'd already taken aboard the landing craft, commanded the coxswain to make one more pass further out. He did, thank goodness. This time they did see us and at full speed approached us with the rubber boat attached to the side of the P.L. The sailor in the rubberboat held out the rope-ring which we put our arm through. Then a team member pulled us in over the side, tugging for all he was worth against the strong surge of the water. We crawled to the bottom of the craft and hastily put on our metal helmets.

The water was cold out around Iwo Jima and the Navy provided two-ounce bottles of brandy for each of us. Shivering from both the cold and from nerves, I was handed my brandy. The next thing I knew one of the men said, "Here, Chief, drink mine." Most of the Demolition Unit was composed of men 18 years of age, none were much over. I was one of the older swimmers being 36 at that time. Even after six ounces of brandy I was still shaking like a leaf. Both my legs were cramped up in knots as hard as steel.

When we got back to our A.P.D., we were told our ship had been shelled about as soon as we'd left her. We had a good laugh listening to our mates tell how they were on the bare decks scrambling to find some sort of cover.

We were happy with the success of our operation. It seems we'd lost only one man who was hit by shrapnel from the mortar which had exploded nearby.

The bombardment continued and Iwo Jima was lighted at night by star shells so gunners could see their hits. I must say we, the Underwater Demolition Teams, were relieved that our part of the pre-assault invasion of the Island was over.

21

Chapter Nine

Withdrawal

Hit

In Tow

Meals

Aboard with us were several Marines who were to observe our engagement. They were noticeably nervous what with D-Day just a day away. All through the day we all seemed in a happy mood, a relieved mood. That evening the sailors were writing letters home to their mothers, wives and sweethearts. Some were playing poker and other card games. The tables in the mess hall on the main deck were especially crowded with young sailors. We'd been ordered to withdraw from Iwo Jima, withdraw to a safer area where we would be protected by a ring of destroyers.

Our Captain lost contact with the rest of the Task Force. We were doing flank speed - the fastest our ship could do. Later we heard that the radar sailor was trying to locate the rest of the fleet. The Captain stood looking over his shoulder. Finally, he told the sailor to step aside and he'd look at the screen. Just at that moment a plane was visible on the screen. It was no bigger that a fly. The Captain did not see it. The radar man did. It was a Jap bomber and it was able to turn around and make another run at the Blessman. When it was seen on the screen, the Captain should have sounded the alarm to man the guns and so have deflected the bomber off target. But, as it was, not a gun was fired and the Jap bomber was then able to center in on us for a direct hit. One bomb dropped alongside us and the other hit the bow of one of our landing craft on the boat deck and the main deck exploding on the deck below. It destroyed the mess hall, galley and number one engine and blew a hole in the main deck 40-feet wide and 60-feet long.

I was sitting in a chair leaning against the starboard bulkhead, reading a book, when the monstrous shock came. The ship, even though doing flank speed, was stopped dead by the hit. The lights went out. The ventilators were belching dirt and smoke. One of the Chiefs hollered we'd been hit by a submarine torpedo.

Now, in any combat zone we were supposed to wear our life preservers all the time. This night, though, I had taken mine off and hung it on a wall. But where? I couldn't remember where I'd hung it. Suddenly, it came to me. It was on the opposite wall. I groped my way to the wall, grabbed the preserver and quickly put it on. I then

22

headed for the nearest ladder and hatch having to wait my turn to climb through the 18-inch hole to the deck at the bow of the ship.

The P.L.S. on the boat deck were on fire, blazing and snapping, making a perfect target for a Jap plane. This would finish us off. I thought sure the ship was sinking and yet there had been no order to abandon ship. I figured I'd take my chances staying with the ship rather than getting into a raft as some did.

By this time, the fire had swept to the troop compartments and to the supply room which contained lots of flammable liquids. We all knew the Blessman was in imminent danger - we were carrying 50 tons of demolition explosives besides all the shells and powder.

Both engine rooms were out of working order. We were unable to get any water pressure for our fire hoses. Bucket lines were formed and from a portion of the boat deck above the fire, huge cans of foam were opened and dumped onto the fire below. Some of the men were desperately trying to start the handy billies which could pump water from the ocean. This failed. An hour later, with the fire dangerously out of control, our Flagship, Gilmore (A.P.D.), with our highest ranking officer, Lt. Commander Kaufman in command, came to our rescue and soon managed to get their hose lines over to us. Then we had that so needed flow of water on the fire.

Next came the task of lowering the casualties into rubber rafts.

They were taken to the Flagship and later transferred to a hospital ship for further treatment of their wounds.

We kept a steady stream of water going over and onto the stern deck hoping to keep the explosives from blowing up. As we fought to bring the fire under control, the 20-millimeter and 40-millimeter ammunition in the storage rooms on the main deck got so hot they kept exploding. This went on for over an hour. Some of us were on the bow. All I had on was shorts and a T-shirt. I was cold. But, still, I was fortunate. I was able to open a hatch cover over the Chiefs' compartment below and get a sweatshirt from my locker.

Out on the bow there was one sailor half alive and another badly wounded. I helped get mattresses and blankets for them and then helped lower them over the side into a rubber boat. I also assisted in the bucket line. Later on I went down to the portside of the main deck, wading in water at least a foot deep, to help put out the raging fire there. The Gilmore kept crashing into the torn side of the Blessman. We were out of control and tossing badly in heavy, rolling seas.

The fire was at last under control and the Gilmore withdrew. They left us and joined the rest of the Fleet.

23

Volunteers were asked to remove all explosives on the deck below. We formed a line and the 20-pound packs of tetratal were handed up and thrown overboard. We worked tediously until daylight and were able to lighten the ship by 15 tons. Believe me, it was some job to get men to go down into the hold. They were, understandably, afraid and leery of leaving the main deck.

The next volunteer-request was to assist in getting all the dead out of the compartments. There were lots of gloves in one of the lockers so we passed them out. Then Ravanholt and I, with several other men who had volunteered, took blankets and ponchos and went into the troop compartments where the burned bodies lay in a foot of water. We rolled the bodies, one at a time, in blankets and dragged them out to the fantail.

Into the mess hall we went where 10 bodies were in a pile. They weren't burned but their clothes had been blown off by the explosion as had their dog tags and shoes.

Each body was wrapped in a poncho with six-inch shells between their legs - all were tied together with sash cord. The Captain, solemnly, read the Burial Rites for each pair as they were slipped over the side of the ship. American flags had been fastened onto the top of the stretchers and the bodies slid out from under these flags each time the Rites were performed. No tears were held back. We all grieved deeply for our lost buddies.

While all this was taking place, we were being towed by a salvage ship and two large Le-Roix pumps were running full force keeping the water pumped out so the Blessman could stay afloat.

The next day the Marines were preparing for the invasion of Iwo Jima and ships kept a continual bombardment of the Island. We on board the Blessman were not conscious of this bombardment but we shall forever remember the day, nonetheless. We were hit with the bomb the night of February 18 and D-Day wasn't until the 21st of February. It took 60,000 Marines to capture the Island of Iwo Jima with approximately 10,000 military personnel and several thousand civilian Japanese. One of our Demolition Teams was called on to blow one of our own landing craft out of the way - they'd been bottled up by Jap gunfire from the beach. A path was blown through these crafts and others were towed out of the way by cables attached to salvage tugs. Our Marines had to literally burn the Japs out of their caves. There was not one solitary building on the surface of the Island. The casualties for the marines were near 20,000, the highest for any invasion in the Pacific.

Anyway, back to us. Another damaged ship took us in tow as the day went on. We were on our way to Saipan. That night we were all out on the main deck. Nobody, I'm positive, slept a wink.

24

The next morning we were out of hearing of the bombardment but were still within sight of Mt. Suribachi. We were only making five knots per hour which meant we'd only traveled about 68 miles during the night. Our grave concern now was that we were no longer covered by our planes and that there was a Jap submarine base only 150 miles away. Our own convoy was made up of crippled ships. We had very little left to fight with.

Coffee in the morning was brewed over a trash can we'd hung over the ship's side. Someone had the bright idea of using some of the large galvanized lockers for stoves. So one of the sheetmetal men cut openings in the tops of three lockers and fixed a grill in the middle. The insides were lined with firebrick we'd taken from our boilers. At dawn we began breaking eggs, one by one, into bowls making sure there were no bad ones among them. We scrambled enough for 300 men - all the men still on board the Blessman. We had quite a time finding enough wood to keep the fires in the "stoves" going but managed by breaking up all the boxes we could put our hands on. Everyone admitted the meal tasted better than those served at regular mess.

25

For the evening meal, we made a huge stew of meat, potatoes and vegetables which were in our lockers and which still hadn't spoiled. Everyone pitched in, even the officers who washed cups and plates for each meal.

We had to black out as usual at 7 o'clock. The supply officer got out his flute and played the sweetest music I'd ever heard. We sang along keeping our tones real low. We all enjoyed those long, lonely hours out on deck in the quiet of the darkness.

I slept out on the bow still wearing shorts, T-shirt and sandals with my life preserver around me, a signal light and Navy knife tied to my belt. We were certainly well aware of the possible dangers - nights were practically sleepless. We were, each of us, jumpy and upset from the bomb disaster we'd, luckily, lived through. Halfway to Saipan, a salvage tug took us in tow. This then meant we were able to make up to nine knots per hour.

26

Chapter Ten

Saipan

Monroe Fox

After what seemed eons, we reached Saipan. Welfare officers welcomed us with an orange, Hershey bar and then gave us evening chow. They escorted us to a mammouth quonsett hut filled with cots, blankets and Red Cross kits. We spent the rest of the day touring the Island. The younger men hunted Jap skulls for the gold teeth. Even then there were Jap soldiers in the hills and every so often they took pot shots at us.

One evening us Sea Bees and Marines were watching movies out-of-doors and some persistent Japs fired several mortar shells into the viewer. A close call.

We were given a tour of Saipan by one of the Sea Bee Chiefs stationed there and this included a trip up on a hill allowing us to see Suicide Cliff over which so many women and children had thrown themselves, tragicly falling onto the rocks below. Up here, too, we were fired on and had to turn around in a hurry and get on back down.

For three weeks we stayed in Saipan. During this time we ate breakfast at the attractive Chiefs' Lounge overlooking the ocean. We bought beer for 10 cents a glass and, if we wished, we could eat a steak dinner at a real low price.

Oh, besides hunting for gold teeth, our men got Jap knives, swords and flags which we suspected the Sea Bees had made themselves.

I want to preface what I'm going to tell you next with this story. The night our ship was bombed at Iwo Jima, Monroe Fox, a member of my platoon, was sitting on his bunk writing a letter. As I've said, the bomb blasted through the troop compartment and shrapnel hit him in the chest and eyes. Well, while at Saipan I went to the hospital and paid him a visit. As I arrived he was leaving. He was blind. The doctors had told him one of his eyes might be saved when he got back to the States. I asked Fox to let me help him to the waiting ambulance. He answered with an emphatic no and to just tell him what direction he should walk in. He further said if he were to be blind, he might as well learn to do things for himself. I asked if I could get him anything. His reply was it would be swell if I could get him a typewriter so he could type letters to his wife. Occasionally he'd typed letters to her and if he could continue to she'd not know

27

he was blind. Yes, I got the typewriter for him and, remarkably, he still could use the keys correctly.

Fox had been writing a book and I'd read several chapters of it. It was destroyed in the fire on the ship. Later, when he was discharged from the Navy, he wrote a book called, "Blind Adventure." After getting home, he painted his house and even was a guide on horseback at a dude ranch where he took visitors trout fishing. He went to college, became a lawyer and at one time was Attorney General for the State of New Mexico.

Twenty-five years after the War, I met Fox, and his seeing eye dog, at a Demolition Reunion held at Fort Pierce. He did say his wife divorced him but he felt not because of his blindness.

28

Chapter Eleven

Pearl Harbor

Maui

Home - Bronze Star

Our transportation from Saipan back to Pearl Harbor was via a PA Supply Ship loaded with Marines who had been wounded at Iwo Jima. The Chiefs on the ship were required to work these men at cleaning chores daily. Some of the wounded were very unhappy doing the work but the commanding officers insisted. When they'd remove their shirts, the wounded men that is, their shrapnel wounds were very obvious.

At Pearl Harbor we transferred to a smaller ship which took us to our original Advance Base at Maui. Here I worked repairing wooden landing craft which were leaking badly.

After quite some time, we got the word we were being sent back to the States and after 30-day leave would go to our Demolition Base at Fort Pierce. We were to be re-organized into a Team again. Incidentally, all of us men who participated at Iwo Jima were supposed to be getting extra "submarine" pay - but we never did get it.

The War ended. Anyone having enough points would not be sent out again. Because I was 36, married and had one child, I remained at the Base at Fort Pierce until November 5, 1945 when I was discharged.

Each of us in our Demolition Team received the Bronze Star for Meritorious Duty at Iwo Jima. Secretary of the Navy, James V. Forrestal, also gave each of us a letter elaborating on the preassault attack on the Island underlining the fact that it was beyond the call of duty.

The secret of the Underwater Demolition Teams was apparently well kept throughout the War. Not a single Frogman was lost in the water and for this we are eternally grateful.

29

Chapter Twelve

Postscript

As I write this story of the invasion at Lingayen Gulf in the Philippines and of Iwo Jima, World War II, a Museum is being revived at Fort Pierce, Florida, which will recount the Underwater Demolition Teams' valiant endeavors.

This circular Museum will house models of Hutchinson Islands where the members of these elite teams trained, as well as models of major battles in which they participated. All the war facts about Underwater Demolition will be shown and this includes old equipment and photos.

The Navy Seals which Frogmen are now called and have been since 1962, will also tell and show their important part in the Navy since World War II.

Dedication of this unique Museum is scheduled for November 12, 1985.

My mother was a four-star World War II Mother with three sons and one daughter.

Thomas - Lt. Comm. in Navy

Edith - Mrs. Hildebrand, Lt. Comm., Public Health, Service of Navy

Robert - Lt. JG. in Navy

Arthur - Chief Petty Officer in Navy

30

Bibliography

- http://secondat.blogspot.com/2010/04/iwo-jima-65-years-ago.html

- Iwo Jima Recon: The U.S. Navy at War, February 17, 1945 by Dick Camp (Zenith Imprint, 2007)

- UNDERWATER DEMOLITION TEAM HISTORIES UDT 15

- WWII UNDERWATER DEMOLITION TEAMS (1943-1945)

- UNDERWATER DEMOLITION TEAM HISTORIES WWII UDT TEAM FIFTEEN

- UDT-SEAL Obituary Records

- Special Forces Roll Of Honour NCDU-200

- The Frogmen of World War II: An Oral History of the U.S. Navy's Underwater Demolition Teams by Chet Cunningham (Simon and Schuster, 2004)

- MORE THAN SCUTTLEBUTT - The U. S. Navy Demolition Men in WWII by Sue Ann Dunford and James Douglas O’Dell (self-published, 2009)

- Navy SEAL History

- National Navy UDT-SEAL Museum

- Bombing of the USS Blessman off Iwo Jima on a website called Fallen US Navy SEALs

- Underwater Demolition Team on wikipedia

- Navsource Online: Destroyer Escort Photo Archive USS Blessman

- USS Blessman on wikipedia

Addendum

Arthur Hettema's group was designated variously NCDU 200 and UDT 15. NCDU stands for Naval Combat Demolition Unit. UDT stands for Underwater Demolition Team. This photo shows NCDU 200. It was probably taken at Fort Pierce in 1943.

Left to right, standing: Elwood E. Andrews (Ensign), William H. McLaughlin (EM2), James E. Matchette (GM3), and Arthur D. Hettema (CCM(AA)). In the front row, kneeling: Monroe L. Fox (SK1) and Lee D. Miller (MM2). Of the group, only Andrews and Fox are mentioned in this memoir. Fox is described in Chapter Ten. The photo comes from the Special Forces, Roll of Honour web site by John Robertson.

Return to Five Generations of the Hettema Family.